Place

K’gari, (Fraser Island) is the (is)land of the Butchulla people and is one entirely of sand. It is the world’s largest.

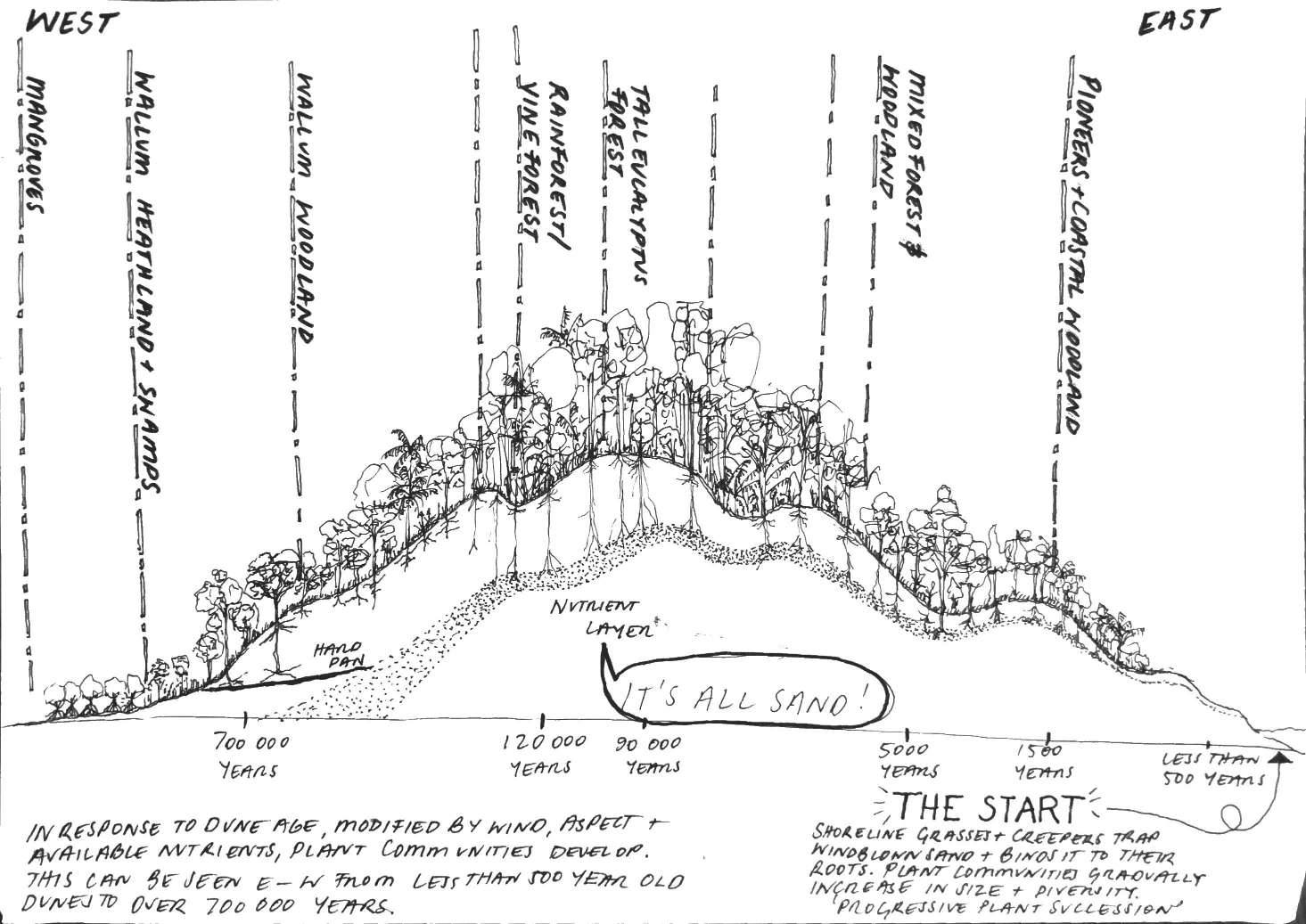

Although a sand island, great diversity exists. The west of the island, the ancient side with calm waters and sinking sand consists of dunes over 700,000 years old consisting of low growing heaths, sheltered tidal mud flats and mixed forest and woodland. HUGE ancient rainforests exist in sheltered valleys thriving on middle aged central dunes throughout the center reaching to what we guessed was over 50 meters tall and houses a terrible amount of mosquitoes. The East of the island is the wild yet ‘new’ side of the island with SE prevailing winds brining sand up the coast of Australia (all the way from Antarctica), constantly forming and re-shaping the East coast creating sand blows and sideways growing banksias. Pioneer plants are the start of all this diversity, taking hold on the newly formed dunes and sand blows, providing a foothold for larger more diverse plants to begin. Analysed through our sections, the eastern settlements; Dilli Village, Happy Valley, Eurong (&more) are nestled back amongst the 2nd and 3rd established sand dunes for protection.

Sounds untouched right? Well it’s most certainly not. K’gari has quite an extensive disrupted history stretching all the way back to Captain Cook in 1770. He sailed past Indian Head (The 25th latitude landmark), seeing aboriginals atop the volcanic rock formation generically named ‘Indians’, named it so.

Land clearing began in Maryborough (on the main land) in 1842. The Island was gazetted an aboriginal reserve 1860 & 2 years later revoked when ‘valuable’ timber resources were found, extraction began. The indigenous could no longer live off the land. This was the beginning of 130 years of timber extraction ending in 1991, of all kinds from kauri pine, satanay to blackbutt. 1950 saw the beginning of sand mining with the largest lease in 1966 covering 8665 HA.

1971 The Great Sandy National Park was created, 1993 native title was recognized and today fishing and tourism are the only extractive activities. Speaking to a middle aged fisherman he told us “When the tailor are here (they come up the east coast to mate in the warmer waters), there are fisherman lined up 150m rod by rod down the beach. You just join the end of the line.”

Don’t even think about cycling here, ever. Only high clearance 4wd’s will get you around.

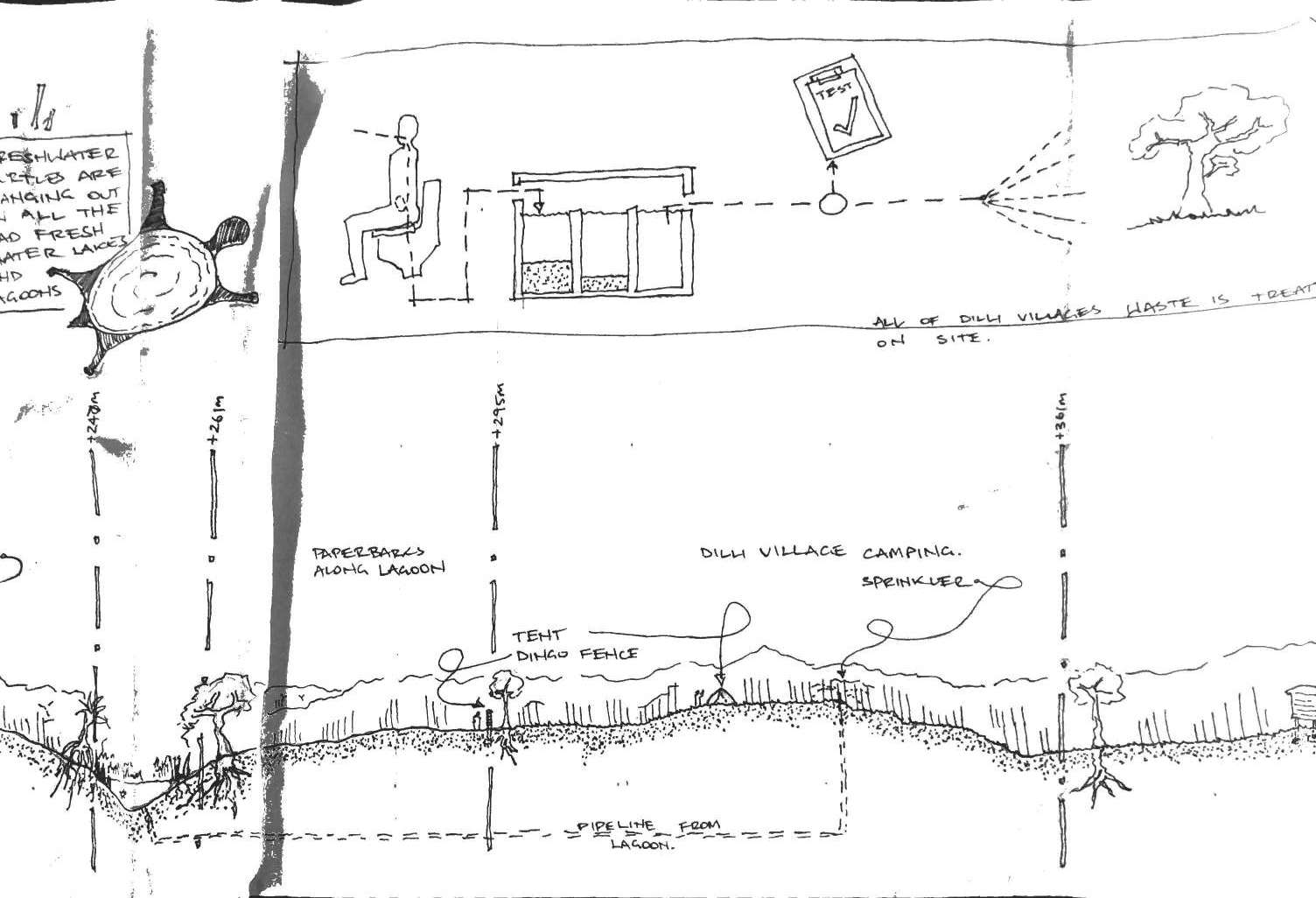

During our ‘off-peak’ stay we partly located ourselves at the private, fenced and off-grid Dilli Village, a freehold land title of the University of Sunshine Coast, Apart from a couple of tourists breezing through – we were it. Basing ourselves here we also covered the island through the day stretching the island, witnessing its diversity, traces of history and ‘architecture’. For the latter part (with no high clearance 4wd) we were based in Central Station, a large clearing which was the headquarters of the forestry operations. It was home to around 30 houses and a school for logger’s children. A huge amount of tourists sweep through there to use the amenities, view the impressively placed staghorns and walk the Wanggoolba creek board walk. What better place for an exhibition, eh?

People

More than 99% of the island is included in the Great Sandy National Park, with less than 100 permanent residents throughout the freehold land titles dotted over sections of the island. Some on parts of the island inaccessible to public, especially to bicycles.

There was a great awareness of place and willingness to share information with every person (of the island) we came across. The island and people are dictated by tides and influenced by weather where these people think about what happens to their own crap and food scraps. Crazy.

A part of what we’re interested in is talking to people who know a place best, and so that’s what we did.

Dianne, permanent resident and caretaker of Dilli Village for the past two years spoke of the challenges of such a place in changing your mindset to fit where you are and how the seasons for her are dictated by the appearance and disappearance of animals, snakes, native flowers and birds. She spoke of the benefits of the villages siting relative to the beach and dunes and other bits and pieces.

Senior Ranger, Anne at Kingfisher Bay is a veteran of 18 years to the place and talked to us not only about the gorgeous architecture of the place but also all the processes behind the scenes such as crap, rubbish, food scraps, dingoes and tourism. She has done all sorts of things, and boy does she know a thing or two.

Stuff (Architecture)

Architecture is varied across the island. Transposed brick typologies along with a majority raised timber, verandered beach cabins, shacks and houses.

Being hard to analyse the questions “What influences how people live”, we added in temporary because for the most part we came across young overseas tourists on tag along 4wd tours and mature solo tourists, a part of tours or shacking up in the sweet Kingfisher bay resort. So we turned our approach to look at how these places work or don’t for the unfamiliar guest, in response to climate, and materials which survive and don’t.

Our analysis found that being amongst the 3rd dune from the beach, Dilli Village rests well where instead of the harsh prevailing wind it’s a SE breeze instead. The toilet block is a cracker, the galvanized steel footings are failing and well, the drawings say the rest.

Kingfisher Bay resort, designed by Guymer Bailey and built 1992 is holding up delightfully (much better than Bobbie at the same age). Using mostly timbers of the island any plants on the site of construction were transplanted to a nursery just km’s away over where the worm farm eats your left overs and your crap gets treated. A lightweight building system lifts the resort accommodation off the ground no greater than 2 storeys (which is lower than the natural canopy) with a consistent basic material palette and structural grid, aiding wayfinding for the unfamiliar guest. Birds and goannas walk under the buildings, water runs off eaves to the plants and watercourses, privacy is well considered with private open space facing natives and the breeze penetrating all. The timber works, the lightweight structure with louvers amongst the canopy is symbolic of the typical Queenslander and the stainless steel fixings with maintenance are the saving grace. The main complex has a grandeur in a beautifully modest way. A contraction at its entry orientates you well, it feels familiar. High ceilings, high louvers with floor and ceiling stepping down to the pool with clear sight lines and geometries give you direction. Privately owned accommodation is for the larger family groups which follow the natural contours of the hills, just as simple in expression. Staff live on site, in nothing as graceful – “dongas”. Everyone wants the air-conditioned one, it looks like a storage container turned esky

The Exhibition we had at central station was a riot! Hordes (well, 60 max) of tourists were dragged by the strategically placed drawings as their tour guide gave them the synopsis of Fraser Islands history in less words than a tweet. Interestingly the older the crowd the more into the exhibition they were. We had one crowd who found that Owen spelt Fraser wrong, laughed and walked off. A tour guide took a photo of our complimentary almonds, made a comment about school children leaving them there and wandered off. A mixed reception at a difficult and diverse site with few permanent inhabitants. Great to be challenged. Next show, bigger, bolder, more formal and larger font!

3 hours into a 6 hour slog (only 15 kms) to the Wanggoolba barge off the island. Through tropical heat (that is sweat not rain), mosquitoes, sand, over grown walking tracks here is a shot of the two happy campers. Bobbie's catch phrase for the day was "get me off this island!"

We pedal on, another town, another exhibition. Hopefully less tourists and more permanent locals and what influences how they live.

Cheers,

Dusty + Thirsty